Article via Australian Broadcasting Corp

I’m of that generation of gay men who remember when the disco lights dimmed considerably in the early 1980s, with the emergence of a frightening new disease.

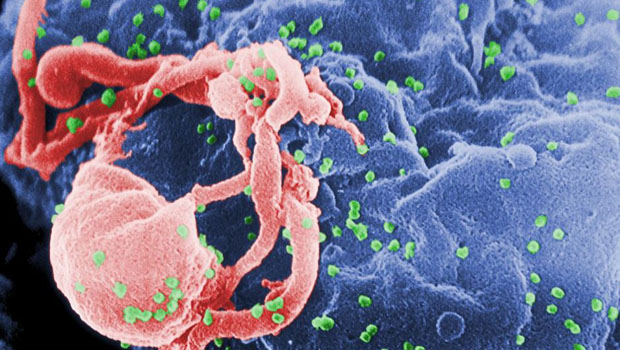

It stopped everyone on the dance floor – a disease without a cure. Worst of all, a disease that attracts judgement and retribution, not empathy and compassion.

The first reported cases of full blown HIV-AIDS that caught the western media’s attention were of gay men in New York. And while blame was not always overt, the sub-text for years was that God had rained fire and brimstone on Sodom and Gomorrah for the wickedness of men who had sex with men.

The day was wet and gray, as I made my way from the ABC, down Sturt Street, to Living Positive Victoria, over a kilometre away from the office.

I was meeting Suzy Malhotra, health promotion manager of LPV – an organisation, which among other things, promotes good practices and well-being of people living with HIV/AIDS in Victoria. Ms Malhotra was generous with her time, to help me understand what the key issues were for people living with HIV-AIDS.

A few weeks prior, I had received an invitation from the UN’s peak HIV-AIDS body, UNAIDS, to join its inaugural Asia-Pacific media network. It’s an informal group of journalists and writers who consider strategic approaches to keep the health issue in the public consciousness.

I don’t have an affinity with figures and graphs but I do respond to stories – human stories. I needed to understand the diverse community living with AIDS, what people go through each day, at work, at play, with family or among strangers.

Suzy Malhotra said the common denominator attached to HIV-AIDS was stigma. In an address five years ago, UN secretary-general Ban Ki-Moon said stigma remained the single most important barrier to public action, saying it helped “make AIDS the silent killer, because people feared the social disgrace.”

It seems little has changed since 2008. One cannot imagine bird flu or SARS eliciting such a response from strangers.

The Kirby Institute recently reported that HIV continued to be transmitted primarily in Australia, through sexual contact between men. In Australia, about 80 per cent of HIV-positive people are either gay men, or men who have sex with men. New HIV infections rose by 10 per cent in 2012, continuing worrying trends of previous years Figures also show that HIV testing uptake is not increasing fast enough, with long gaps between people contracting HIV and when they’re diagnosed.

Is the message not getting through? Are new generations of gay men oblivious to the dangers of unprotected sex? The dangers of sharing needles? Is it because being HIV-positive need no longer be a death sentence, thanks to the armoury of drugs now available, toxic though they may be?

Gay men of a certain vintage in Melbourne remember what it was like during the early days. They remember when Fairfield hospital (now closed) was a frightening prospect, despite the valiant and often compassionate work of the staff there.

Youth may be wasted on the young, but it also poses dangers – misplaced confidence and feeling of invincibility, that science and modern medicine can fix it.

It’s that state of innocence, of being spared the loss of a mate to HIV-AIDS. When the luminous Elizabeth Taylor courageously supported a dying friend, the film idol Rock Hudson, she took on the greatest role of her career – that of AIDS activist. This, against a backdrop of 1980s political and social hysteria surrounding HIV-AIDS.

Elizabeth Taylor and Diana, Princess of Wales continue to be admired by many gay men, not just for their fabulousness, but because they had lent humanity to a terrifying disease. Elizabeth Taylor through her stellar work in AMFAR, the American foundation for AIDS research, and Diana for her tireless fund-raising. And for putting a comforting arm around a dying gay man, in an instinctive act of empathy.

Decades later, people living with HIV-AIDS still need a hug. People still ask, “how did he get it?” As if the mode of transmission somehow determined how one graded the patient on a pity scale – from a high-score of contaminated blood transfusion (poor sweet, not his fault) to a low score of unsafe sex (what a stupid slut).

The 2013 Inaugural Meeting of the UNAIDS Asia Pacific Media AIDS Network aims to tackle issues of stigma, dialogue and public awareness, putting HIV into context along with other health and development issues.

The research foundation that Elizabeth Taylor helped set up, AMFAR estimates that every ten minutes, someone in the US is infected with HIV. It’s a health issue that is not about to go away, not even for wealthy developed nations.

Note: This article does not necessarily represent the opinions of Paul Morris or Treasure Island Media. We felt it right to post, allowing each of you to digest, and form your own opinion. We look forward to hearing what you think.