— James Baldwin, Giovanni’s Room

I remember watching Christopher Rage’s MANHOLES for the first time. It was the only Rage tape I’d seen and the circumstances were almost perfect: I was in San Francisco with a buddy and we were both thoroughly fucked up. We’d chuckled when the clerk at the video store had commented on the fact that we reeked of Crisco.

MANHOLES isn’t his best or most powerful tape (that would be FUCKED UP). And it isn’t the most evocative or personal of his tapes (my choice for that: MY MASTERS). But MANHOLES was the first Rage tape that I saw and it’s a real piece of work.

We popped it in, and when it began with a love song I frowned. A sentimental gaysex video? I’d seen enough of those and wasn’t in the mood for another. I didn’t know yet that Rage had written the opening song, and that he’d been a serious songwriter (serious enough to have had one of his songs recorded by the legendary 70’s group the Spinners; and serious enough to have learned early on that the music business was far slimier than porn).

But despite the fact that MANHOLES was opening with a love song, the first image in the video was…I remember grinning and saying, “Now this is something.” A hairy arm; a close-up of a man’s hand deep inside his own ass. The hand slowly pulls out. I grinned, realizing what Rage was about to do. The hand covered with slime and Crisco opens to reveal a piece of paper. The paper is unfolded and there are the credits for the tape pulled fresh from a man’s ass. Yes! This was an opening worthy of Samuel Fuller (had Fuller done sexfilms). We applauded drunkenly. We cheered. We fucked.

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

A few days before, I’d seen a performance by queer performance artist Keith Hennessey. Hennessey and another performer had been nude. The other guy bent over and Hennessey put on rubber gloves. He touched the guy’s ass and feigned reaching in. He opened his gloved hand and there was a piece of paper with a predictable political message on it. Bland, sterile and safe, it was a perfect instance of gay/queer art being less realistic and less committed to the physical exigencies of life than much porn.

Rage had seen the idea through in the way that it demanded to be done. Furthermore, he accompanied this extreme gesture — tossed off generously as the credit sequence — with a romantic song. It’s an emotional dissonance that at first seems to be insurmountable: we see a man alone, fisting himself; we hear a tender love song. But it becomes a working juxtaposition when one does what Rage requires: take whatever you’re given and connect.

I’d like to briefly consider four videos, one of which Rage wrote and starred in, and the other three of which he produced as his own work. This paper is necessarily a cursory consideration of a few works by one of the more creative and neglected figures in 20th century American culture.

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

DRIVE! (1974)

Under the name Trey Christopher (his Actors’ Equity name — “Trey” was a childhood nickname; “Christopher” is from Christopher Street in NYC), Rage wrote the screenplay for Jack Deveau’s DRIVE!. The title refers both to the male sexual drive and to the fact that the hero of the movie is always tooling around Manhattan in a Lamborghini. Coming on the heels of the period of “art-house” film, during which pornography was intermixed with “underground” and experimental cinema, it lacks the rich creative sexiness of much of the work that was made in this earlier period. Nevertheless, DRIVE! has high production values (a nicely composed theme song, many elaborate set-pieces and so on), some well-directed orgy scenes and valuable near-documentary glimpses into the world of mid-70’s gay life in New York. Studflicks listed it as one of the “top 100 gay porn films of all time”, and described it like this:

“The closest gayporn has ever come to a James Bond movie, DRIVE!, with 56 people in the cast and dozens of locations, mixes a preposterous mad-scientist plot with sex tableaux at every turn.”

In an interview for the magazine Skinflicks, Rage discussed how he came to be involved in the making of the film:

“Arch [Brown] introduced me to Jack Deveau, who hired me to write for him and do his publicity. One film that I wrote was DRIVE!. I was also doing publicity for a theater that Jack owned where THE DEVIL AND MISS JONES was playing. We were trying to get Lynn Carter to star in DRIVE as the villainess. Well, Lynn couldn’t do it and Jack decided that I was evil enough to play the part, so I wound up being cast. It was a really campy movie, not particularly sexy, but campy.”

In the film, Rage, working under the stage name Mary Jim Sstunning, played the drag part of Arachne, a sinister villainess and the proprietor of a decadent cabaret. Arachne has a secret mission: remove the sex drive from all men. She’s been working on achieving her goal through the castration of as many males as she can capture. But a scientist has discovered a formula that will permanently remove the male sex drive, and Arachne is intent on getting the formula.

Late in the film, Arachne sits alone in her dressing room, gazing into a mirror, holding a glass bottle in which a severed penis has been preserved. We hear her thoughts:

“I was not always beautiful, was I? I was not always so certain about what needed to be done. I know I was not always alone. There was a time when I couldn’t bear to be by myself. Before I met my loyal Androgyny [Arachne’s submissive henchman], I would search men out, hungering for their company — eager to touch, and to be touched. It seemed I was always cold. My bowels were tight with the need for warmth and I looked always for a man whose passion was greater than the chill I felt inside me.

“Like many of the other animals, man is predatory — or so I have been told. But it seems that unlike the others, man hunts when he is not hungry and kills only for the thrill of it. There is no motive or reasoning behind the hunt and there is only limited pleasure in the kill. An immediate release, but never something to be savored. And even before the blood is dry, man begins to hunt again; not knowing or caring if he is hungry. Insatiable, searching, conquering again …

“It was not long before I forgot the reason I was searching. I would scurry out at night without thinking, bent only on finding another body. And if I found one man, and if he did what he could to satisfy me, then I would look for another man. Each of my men was beautiful — this man more beautiful than the last man, the next man more beautiful still; but it made no difference to me how beautiful any of them was. I wanted more. I wanted them all. For as long as I kept looking, I never worried about whether or not I would find …

“I hunted at night until it wasn’t enough to hunt only at night, and then I hunted during the day too. I couldn’t stop. I didn’t want to stop. My thoughts were only of hard bodies, rigid with the desire for me — beautiful men swollen with the need for me. They were all around me and I chose the ones who looked most eager.

“Until I saw a man who was so perfect, with a hunger in his eyes that reflected my own hunger — and I knew he was the one. I knew we could feed from each other, claw at each other with a need we didn’t care to understand.

“Drugged with desire for each other’s hot naked skin, tense muscles pushing — and then filling me with his need, white and hot. Crushing me with his strong arms, pressing down on me and into me, until I closed my eyes with the ecstasy and perfection of him, and I screamed for him — and I screamed for me.

“And I opened my eyes and I was alone.

“And I vowed then that I would bring an end to it all. Man would have to search no more: Arachne would be the answer.”

A telling document by and about Rage. He wasn’t Christopher Rage yet, but certainly this lengthy soliloquy holds elements that would lead to the construction of the “Master of Sleaze”: a relationship with sex that’s both consuming and consumed by guilt (it’s an unreasoning search for impossible satisfaction); an equating of sex and death, of sexual conquest with destruction, of desire with helpless compulsion, and (in the opening sentence) of sexless androgyny with beauty.

According to Kenton Neidal, Rage’s lover and business partner through much of the 80’s, Rage defined “sleaze” as “the ability to uncover what a man wanted to do but was also unwilling to do … and finding the way to get him to do it”. A testing of the boundaries among will, desire, guilt and self-definition. The interplay between desire and will, between sleaze and guilt was to be central to all of Rage’s work.

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

SLEAZE (1981)

In the Skinflicks interview, Rage talked about the beginnings of his own film work, setting the film SLEAZE as a turning point:

SKINFLICKS: Do you think your films are controversial?

RAGE: Evidently. Not to me, though. I certainly didn’t set out to make controversial films. The first ones that I made were pretty straightforward. And then I made a movie called SLEAZE.

SKINFLICKS: That was a very high quality film.

SLEAZE is the first flowering of Rage’s style. In contrast to DRIVE!, the narrative framing (called “webbing” in porn) is minimal: an old warehouse in NYC has been taken over by a group of men in order to set up a private underground sex club. To belong to the club one is only required to have sex with one of the members.

It’s not the idea of a sexually-based club that makes this film exceptional: ritual membership in secret sexual groups is a common premise for gay porn. But in SLEAZE, Rage has taken a remarkable stylistic leap. He works seriously with the specificity of the “scenes” in a way that had never been done before, giving each its own soundtrack, style and eccentricities. It’s the first glimpse of a world that Rage was beginning to create.

SLEAZE was the last of his films to use outside establishing shots. After SLEAZE his work was exclusively about the indoors. Even in SLEAZE, the exterior shots serve only to contrast the outside world with the insulated, secret interior that in later pieces Rage (and his audience) took for granted. From this point on, Rage’s project was guided by the need to create a world that encompassed the extremes in which he was interested and that simultaneously seemed absolutely believable and real to the audience. This indoor world was his theater, his laboratory. It also was a way of defining his territory in contrast to the work of West Coast pornographers like William Higgins (whose work he hated) who specialized in wholesome golden-boy films that were saturated with sunny daylight, tanned muscular men and vanilla sex.

I’ve written elsewhere about the complex language of signification found in porn videos and, in particular, in their soundtracks. In Rage, the soundtracks are particularly important. In the interview in Skinflicks, Rage discussed this:

SKINFLICKS: Who cuts your films?

RAGE: I do. I shoot them, I edit them, and I do the stills, the advertising. You name it. I write the songs, I sing the songs, everything.

SKINFLICKS: Your sound work is particularly impressive.

RAGE: I think that’s an integral part. I learned that early on. I think that sound is so important.

SKINFLICKS: That quality is often lacking in many big budget pornfilms.

RAGE: In most of them. They’ve got these gorgeous, incredible people, with these dicks that must be implants, and they spend…I read somewhere that Al Parker, someone whom I’ve never worked with that I adore…said the average gay film costs ,000. That is so far out of the league of what I do. And then they blow it by putting stupid soundtracks on them.

This situation is unchanged today. For the most part, the larger producers of porn ignore soundtrack design, slapping on bland industry-produced music that has no connection to the action or images. In Rage’s videos, the music fits the images with remarkable (and, for porn, incomparable) intimacy and expressiveness. Rather than making use of the usual repetitive musical “loops” that were (and are) used in much porn, Rage’s music is often extremely specific, virtually physicalized in the expressive connections of sound-to-image or sound-to-act.

In SLEAZE, each room in the warehouse seems to have its own musical style. Furthermore, Rage edited the soundtrack with the visual cuts. As the film moves back and forth among the various scenes, the soundtrack changes completely and precisely with each cut. There’s no transcendence: the music is inseparable from the action. There’s no attempt to use the music to construct a segue, or to link scenes together, to provide continuity. It cuts and jumps with the edits; non-diegetic yet tied to the sites depicted on camera, the soundtrack seems to be defining the physical videotape itself as the diegesis.

Rage’s musical style (his pop songs notwithstanding) seems to be strongly influenced by the downtown experimental sound of the period. This sets it apart from the soundtracks for big-budget gay porn films of the 70’s (such as those of Jack Deveau). There is no apparent connection between Rage’s music and any of the four musical styles favored by the porn-auteurs of the 70’s: classical, faux-Hollywood, Broadway, disco. In a great creative leap, Rage opened new territory for sex music: independent, experimental, idiosyncratically expressive. This crossing-over reflects not only Rage’s independence, but also the (at that time) new social philosophy of homo-sex. It was proud, it was breaking with tradition, it was strong enough — and complete enough — to create a world of its own, independent of references to any music that had previous been understood by audiences to be explicitly gay-oriented.

The soundwork is certainly not invariably wonderful. He wasn’t above taking a soundtrack that had been meticulously designed for one video and laying it over a completely unrelated segment of a different video (promiscuous, after all, and sleazy). But the work can at times attain a level of clarity that’s undeniably brilliant, comparable in expressive inventiveness to the best work of “serious” artists contemporary to Rage.

For example, Rage on occasion played with stock porn sound-techniques. In SLEAZE, the soundtrack to a scene between Casey Donovan and another performer is a porn dialogue that has been so thoroughly electronically modified as to seem defective. (And in fact customers complained, thinking that they’d received defective copies.) The connection of the dialogue we’re hearing to the two men we’re watching is unclear: it might have been lifted from another porn film altogether. And the rich response the track evokes is due in part to the fact that it’s impossible to know if we’re hearing the modified voices of these or other men. But what at first seems to be either technical ineptitude or a sleazy use of someone else’s soundtrack is slowly revealed to have been a carefully designed effect.

At first it’s extremely difficult to understand what’s being said: the distortion is too great. From the rhythm and the guttural tones, though, we can tell that the dialogue is sexual. At the conclusion of the shot, bits of sexual dialogue come out clearly: Casey Donovan saying, “You want to fuck my ass? You like that ass?” distorted to the point where the effect is as eerie as it is sexual. We’re given a cold, creative vantage point, not knowing how to gauge the reality of the moment, having to find a way to make it work by engaging actively with the material. It’s pornography reflecting itself, using the cliché of the interchangeability — the inherent promiscuousness — of its own parts to augment the exciting anonymity of the moment. It tells us two things: (a) that it knows what we expect “real porn” to sound like and that it can expressively play with our expectations, and (b) that it knows that whate

ver it gives us, we will assign these voices to these bodies. The viewer’s willingness to assemble even random elements into a workable erotic configuration is the central phenomenon on which Rage built his work and style. He plays with the hungry complicity of his viewers, engaging them in the sleaziness of the videos. Being sleazy is having the ability and the willingness to become whatever is necessary to get what you want. Or, conversely, to somehow make whomever you’re with into whatever you want — or need. It implies a very basic malleability of selfhood, a flexibility of identity that’s less depersonalizing than it is repeatedly repersonalizing. Take what you’re given and make it work. This is the exercise of sleaze.

Rage’s creative — and perfectly sleazy — relationship with male sexual response is defined by the distance between what we want or expect and what we are given. Over and over — in his choice of men and soundtracks, his choice of act or practices, “scenes” or sets, his filming and editing techniques — Rage tells the viewer, “This is what you’re getting: let’s see if you can make this work.”

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

OUTRAGE (1984)

OUTRAGE begins with a close-up of a painting of Rage by Victor Obuchowsky. The credits that follow are handwritten on pieces of cardboard pinned to a wall. The soundtrack is far more “worked” than the videotrack. As in SLEAZE, it’s reminiscent of experimental music: electronically altered voices in an audio collage full of reverb.

The painting of Rage sets his presence in the film and jokingly connects the video to “art”. In the context of the impoverished pushpin and paper clip credits, this self-promotional moment is a parody of artistic egoism. Rage tacked things on the wall, pointed the camera and shot. He happened to be one of the things tacked up.

As usual, he follows the credits with a brief introductory “set-up”. These narrative bits were added after the rest of the video had been shot, yet they feel integral to the rest of the video, as much because of Rage’s charismatic presence as anything else.

In the opening of OUTRAGE he tells a story: as a kid he used to camp out in a vacant lot with his buddies. They’d play around, sometimes sexually. He ends the story by saying, “I’m sure no kid now, but I still like to play games.” This sets the tenor of the video: it’s play, and it’s a kind of play that derives from childhood games. That this creates an air of innocence is important: Rage wants to consider what follows to be not only sordid sleaze but also innocent play. And we are tacitly challenged to do the same. (This was to be a primary theme of his journals as well.) One can imagine the Catholic Rage asking us — and himself — “Can we do these things without guilt? What about them inspires guilt if they’re only play?”.

A real wonder of his work is its rich improvisatory immediacy. In the first scene in OUTRAGE two men shave each other’s bodies and heads with electric razors. They stand in a makeshift set of strung canvas. “Fuck me” and “I love to suck cock” are painted on the canvas. The “set”, such as it is, resembles an exploded tent and in this context seems intended to work with Rage’s set-up involving camping out and playing.

One of the two men doing the shaving is J.D. Slater. With no conclusion (i.e. no “money” or come shot), there’s a sudden cut to Slater alone with a young boy. Slater plays roughly with the boy, concentrating on his nipples, causing real pain.

Another sudden cut, and we’re in the same room with the same submissive boy but a different top-man. Now the boy’s hands are tied behind his back. After only a few seconds, Rage suddenly cuts to an unrelated shot for which we can’t be prepared.

It’s a slow pan down the body of a man who is standing with his hands bound above his head. He’s wearing a leatherman’s motorcycle cap (macho); odd futuristic slit-sunglasses (stylish); a plain white shirt, open and knotted in front (calypso y femme), crotchless red lace women’s panties (muy femme); leather cock ring (macho); rolled down sheer nylons (girlfriend!); tooled leather cowboy boots (macho). The man is almost an emblem of Rage’s excessiveness, his drive to confuse our well practiced sexual semiotic, our code for reading sexual behavior. What does this bound man want? What is he “saying”? It’s impossible, really, to know. And to make matters even more complicated, Slater walks in, wearing a knotted-cloth primitive woman’s bikini. Wilma Flintstone at the beach on acid wouldn’t seem so strange.

Slater sucks on and tortures the genitals of the elaborately dressed bound man (who happens to be Rage), and the viewer is shoved unceremoniously out to sea. He must either give up and lose interest (“too weird”) or construct a way to react. The scene demands active spectatorship.

A bit later, Rage cuts back to the submissive boy, who is now sucking on a leatherman’s cock. The cock never gets hard, but no one seems disappointed. The scene changes, suddenly, to Slater again. He’s masturbating, standing in a blank gray space, watching a video monitor. On the monitor is what we (the camera and the audience) are seeing. An exhibitionistic set-up: Slater is aroused by watching himself becoming aroused, knowing that we — the men who are watching — may also be aroused.

Another sudden cut back to the submissive boy who is sucking on yet another soft cock. Then an abrupt jump to two men in front of a bright lemon-yellow backdrop. One of the men puts a rubber on the other’s big, erect cock. But he accidentally puts it on inside out. Rage keeps the camera rolling and doesn’t edit the scene. We watch the interminable effort and feel frustration as the rubber simply won’t do what it’s supposed to. Putting on the rubber incorrectly, ineptly, becomes a project in itself. This openness to unexpected or inept behaviors, this willingness to savor what others would term error or accident — I know of no other pornographer who wouldn’t have edited this scene out — sets Rage apart.

After an infinite amount of time, the condom is on, covering the huge erect cock. The first man plays with it, biting at the condom, pulling at it, stretching it, tearing holes in it. After much play, he pulls it off and puts another condom on the second man’s cock (this time rightside out). And this time he stretches the rubber over the second man’s cock and balls, then plays with the whole generous set for a while.

Clearly, condoms are the play-theme for now: cut to two men who stretch rubbers over their own cocks and balls and then play for a while and suck on them, biting and tearing the rubbers in the process. Then cut back to the first two men who’d played with rubbers, the men with the lemon-yellow background. This time the second man is putting a red rubber condomish thing with projectiles onto the cock of the first man. The men are calm, impassive, in deep concentration.

After only a few seconds of this, there’s a cut to two other men masturbating, and the condom set is over. At no point in this sequence of episodes were any of the condoms used for “protection”; and there were no ejaculations. This, after all, is play.

In a later scene from OUTRAGE, the interaction between J.D.Slater and Rage has the feel of an explicit if minimal ritual. The scene opens with Slater nude on his back on the floor. The backdrop is black. In the foreground are several rows of unlit candles. In the soundtrack we hear off-camera coughs: we’re privy to the making of the scene, as well as to the scene itself. Music starts, melancholy piano music in F# minor. It’s slow and moody, completely uncharacteristic of porn soundtracks.

As the music continues — mixed on the soundtrack with the machine noises of the filming equipment and the ambient sounds in the room — Rage lights the candles. There are around thirty-five candles (Rage was probably 35 when this was shot, although he often lied about his age), and this takes a good amount of time. The music becomes recognizable as a slow, melancholy version of Rage’s song “Animals”. It’s a simple and haunting song that Rage uses many times and in various videos. Although the version used in this scene is for solo piano, it’s useful to know his lyrics for the song:

What kind of animal are you?

Literal or metaphorical,

What kind of animal are you?

Of all the animals,

The one most bestial

Is never put into a zoo;

Animal, what kind of animal,

What kind of animal are you?

Physical or metaphysical,

To growl and groan with you,

Cannibal: it’s understandable,

If that’s what appeals to you.

Animals, all men are animals:

What kind of animal are you?”

After lighting all the candles, Rage moves behind Slater and drips hot wax from a candle onto his belly. To ameliorate the pain Rage shoves his cock into Slater’s mouth. Slater sucks in the soft dick in a manner that’s only secondarily sexual.

The wax drips, Slater shouts in pain, Rage talks him through it. And the melancholy music plays on. Suddenly the scene is over with an abrupt cut to a man shaving a bound man’s crotch. With the cut, the music changes: it’s the same tune, but now stylized, modernistic and synthesized, the tone utterly different. In the previous scene, the use of the minor-mode piano music had the effect of setting a connection of emotional intimacy between two men. Throughout the scene, the music works to keep us from becoming sexually aroused, holding the viewer in a mode too contemplative and moody to be arousing.

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

KISS IT (1989)

In the opening of KISS IT, perhaps Rage’s last video, a group of men are kneeling in a circle, kissing. We hear ambient sounds — licking and kissing sounds in a dark resonant room. The (non-diegetic) music consists of a slow melody of synthesized tones, low and eerie. The melody stops, begins again, stops: its haphazard entries seem unrelated to the action. A man gives someone sexual instructions, repeating his words over and over. The sparse music, now an open fourth, now a single melodic line, frames the talk with an aura of monastic seriousness.

The camera slides in among the men, viewing the group closely, inspecting them: we’re intertwined with the group, completely involved. Suddenly: Beep! — a car horn from outside. The sound completely disrupts the scene’s atmosphere. And yet Rage didn’t edit it out. Rage never edits them out. We’re in a city and life is going on outside. The accidental car horn seems to be almost a trademark sound for Rage, a way of breaking whatever porn trance we’ve been lulled into.

A sudden cut to a theatrical shot: on the left four men are having sex. On the right a young blonde boy is alone, masturbating. Close to us and in the middle of the room, a disconnected toilet — a prop and a symbol. The shadows of the men fall across the solitary boy. After several sudden edits, we see the same blonde boy, close and from the rear: he’s bent over and plays with his asshole. Very faintly we hear…a Bedouin song? An Islamic chant? It’s impossible to tell what it is, exactly. It’s a moment reminiscent of the fireside scene from Gus van Sant’s “My Own Private Idaho”, in which American Indian chanting is heard faintly, inexplicably, as River Phoenix talks with Keanu Reeves about love. The effect in both works is that the erotic context is given a faintly surreal and exotic aura.

We jump to the men across the room. There’s no sense of progress or development. The edits lose us in messy time: one thing just happens after another.

A sudden cut to another emblematic set-up. The boy has disappeared: the four men are arrayed on a stairway that goes up to the blank face of a wall; and a handsome submissive man is sucking them off, one after the other, slowly moving up the steps on his knees. In the soundtrack we hear two of the men talking about how the sucking man needs training, loves to suck cock, and so on. A slow monodic melody is being played on a synth using a low male-voice choral patch. The effect is dark and serious, almost sepulchral. As is so often the case with Rage, the weight of the scene nearly overwhelms the simple act that is its rationale: all this is about sucking cock? All this weight, all these symbols, all this seriousness?

“A man’s gotta do something”, a character in the video says. (It’s Joe Simmons, a model Rage introduced to Robert Mapplethorpe.) These men move in a world where doing nothing would be a real possibility. Disconnected from the rigors of a work ethic, it’s a foreign place in the middle of ambitious America. In this room it’s pure drive, no ambition.

Rage often plays with the identification of one part of the body with another. Later in KISS IT, for instance, the blonde boy is masturbating while facing a mirror. As the camera goes in for a close-up of his cock, there’s a sudden and brief voice-over from another of Rage’s films, the infamous FUCKED UP. It’s Casey Donovan’s voice saying, “Get in tight on my face, Trey.” (“Trey Christopher” was another name Rage used.) Donovan’s voice repeats this several times.

This use of his voice not only intimates that the boy should ejaculate onto Casey Donovan’s face (which is, of course, nowhere: he’s in a different video), but also suggests that what we are looking at, i.e. a cock, is a man’s face. This is followed by an extended segment that cuts back and forth from the blonde boy with a mirror to the same boy with the four other men. The effect of this repeated alternation is that the grouped men are equated with the reflection of the solitary boy; and vice versa: the narcissism of the boy is reflected onto the group of men having sex. The group and the individual are in some sense the same thing, the same phenomenon translated through the mirror of sexual desire.

The soundtrack for this segment is an overlay of voices from other films — MY MASTERS (Scott Taylor-Hampton’s voice) and, again, FUCKED UP (Casey Donovan’s voice), in addition to quiet aimless melodic improvisation on the piano (music that is “going nowhere”). The effect is dark and hypnotic, playing with time, as though time in Rage’s universe is created by random washes of desire. When KISS IT was made, both Scott Taylor-Hampton and Casey Donovan were dead, yet here are their voices in a pornvideo soundtrack. Rage’s timing is perfect: as he cuts to a close-up of the boy’s lips (the boy is saying “Kiss it … yeah, kiss it …”), we hear Casey Donovan saying “Yeah … nice close-up!”. It’s a montage of sex and death, hermetically composed and hidden in the sleazy context of a porn video. When KISS IT was made, Rage had a year to live.

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

CONCLUSION

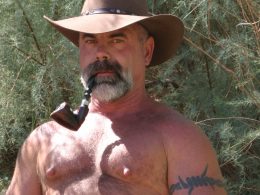

When a friend showed me a photo of Christopher Rage, I looked at it carefully. There was a coy guardedness and insolence that I immediately identified with. He was unshaven, wearing a T-shirt and a cap. His direct gaze was vulnerable yet confrontational, a sign of an aggressive and controlling bottom. With his thumb in his mouth, you could almost hear him say, “Wanna be in a dirty movie?”

This, I thought, was a man who put a good deal into his meetings with the camera, whose presence would invite extremes, whose attitude would carry more than enough rope. Within the gay world he was anathema: in an interview he said, “I actually met somebody who wouldn’t shake my hand. They were afraid to touch it.” He added, “That was obviously not somebody who likes my movies.”

What was it about his work that might cause such a reaction? The material was extreme: within the circles that know of him, Rage is remembered as the “Master of Sleaze”. In addition to hardcore straightforward sex, he dealt with fisting, scat, piss, torture, blood, Satanism, death. And there was the man himself: Rage was driven and difficult. Kenton Neidal described him as “a man who had no stop mechanism”.

But I would guess that the single element that made his work so off-putting to many men was his style, a style that developed as a result not only of erotic vision, but also of necessity. He was never free of financial worry, so he worked constantly and often in a rush. In the Skinflicks interview he talked about an early phase of his career, when he wrote porn novels:

RAGE: Well, I don’t know if you’ve ever done any “grinding it out” but … [laughs]. I was twenty-one and I could sit down and write a book in two days. In fact, my record was two books in three days.

SKINFLICKS: Not bad.

RAGE: And it was straight pornography, which I knew nothing about.

It takes strength and nerve to “grind it out”, without the luxury of time and the resources that come with wide acceptance and money. Inconsistency and compromise are signs of work made under duress, yet in Rage’s work they blended with his brilliance and led to a style that incorporated many elements that prefigured postmodernism. Such elements would include non-linear organization, an interplay of subjective and objective stances, a mixing of professional style with amateurishness, incorporation of high- and low-tech in the same video, occasional random inclusions of unrelated and extraneous material of various styles.

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

In the journals written after retiring from New York in 1989, Rage wrote a great deal about his midwestern childhood and about his early sexual explorations. And he gave his ever-watchful mother the (cruel) nickname “Hawkeye”. Much of his early sexual experimentation was circumscribed by the need to craftily elude Hawkeye’s constant scrutiny.

11/25/85

“When I was eight and nine and ten, I already considered myself something of an expert in the craft of seduction. I had been caught at four for the first and only time by Hawkeye and had adopted rule number one. It’s only good if you don’t get caught.

“Hawkeye was relentless in her policing of my activities. I realized early that her instinct for the correct question made it necessary to avoid being questioned at all.”

Predictably, the importance of things that are hidden and secret became a primary theme in much of his work. In the porn videos men are situated in rooms within rooms. Windows are covered. Men’s faces are hidden; voices are distorted. We really never know where we are. Even his editing style kept the viewer disoriented and uncertain.

Furthermore, he constructed in his adulthood an occulted identity that was more or less impossible for anyone to police. When he moved to New York as a young adult he went through a series of transformations. His career and his name changed a number of times. In this process he shed the restrictions of his background, of his history, and built a flexible and untethered new persona. Without this constructed distance from the child he had been, the transgressive work that established his reputation couldn’t have been done.

Anonymity, promiscuity and creativity are all mutually enhancing, and Christopher Rage embodied all three. He lived in New York where he could be as anonymous as he liked. He briefly tried living on the West Coast, but hated it. “In LA,” he sneered, “after two weeks you know everyone, and everyone knows you.”

Ultimately, the idea that most interested Rage was that of the animal inside each man. It’s against the unfettered freedom of this animal that our culture — and our parents — enforce the development of a workable social persona for each of us. Uncovering and awakening the animal — eluding Hawkeye — was both the intent and the result of what Rage called “sleaze”. He often said that he filmed people who needed to do what they were doing, whether the camera was there or not. The videos present men as elements within a sphere of desire so consuming as to render them volitionally impaired. Perhaps they don’t want to be doing what they’re doing, but they just can’t stop themselves: the animal is in charge.

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Nearly every aspect of his work was an homage or a deference to the animal. The coherent or logical overview, the sense of a controlling authority was consistently removed or avoided. As I mentioned above, the “themes” for his videos were added after shooting was finished. And in general, the shooting was done with no organizing principle. He would let the camera roll, capturing everything. Later, he’d edit out scenes or moments that were similar or related. A shoot that lasted several hours might be edited into any number of variously usable segments, some lasting only a few minutes. At the end of months of taping and editing, Rage would come up with an idea that might tie a group of scenes and images together. The “theme” of a video, then, like the “identity” of a man, was secondary. Both were important only as conventions to play with, abuse, demolish.

But there is, in fact, an uncanny continuity in each tape. Not a narrative (in the sense of being “narrated” by a character or organized by a story), but a contextual and nearly cubistic movement, as though seen from a number of different points of view.

And, again, his sound tracks augmented this, usually in one of two ways. First, they sometimes connect with the specific physicality of an act. (In one scene, two men put clothespins on each other while in the soundtrack sharp synthesized attacks aurally underscore the pain the men feel.) And second, they can introduce emotional material that is so radically at variance with what one usually associates with video sex that the viewer is challenged to rethink his reactions. The result can create such a strong emphasis on specific moments, acts or scenes that overall continuity is lost.

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Surprisingly, what’s most important in Rage’s work isn’t the sex (which isn’t to say that the sex isn’t important!). What’s most important is the sense of realness and of pure life in the connections among men. I’ve talked with many men who’ve told me that they love his videos — own them all — but were never sexually aroused by them. But this isn’t really surprising. In the world he created, pleasure is a tool used for the construction of situations in which the body is the locus of meaning and identity: the men in his videos are saturated with their own physicality. Not because they’re especially talented or beautiful, but simply because they are men. In Rage’s world, and in contrast to the “real” world, simply being a man is enough. And because of this, these men are cut off from the ordinary world, the world of public identities, the world outside Rage’s sparse interiors.

Watching a succession of video works by Christopher Rage, I’m struck by the sense that what I’m seeing is less pornography than catalog. Each video depicts manifold possibilities that can result from the simple occasion of men encountering each other physically outside the strictures of ordinary sexual behavior (those, for example, biased toward genetic reproduction). In the freefall space within which these videos take place there exists an infinite number of acts and configurations to explore. In his journal Rage said that he wanted to be Rosalind Russell. Certainly he meant Russell in the role of Auntie Mame, since the videos are glimpses of an abundance most men haven’t the courage or wherewithal to approach.

Rage wasn’t an accomplished videographer. He wasn’t an accomplished composer. His talents in making porn were relentlessly amateurish. But he was a master of redefining and rediscovering modes of sexual connection. Better than anyone before or since in male pornography, he understood that finding and crossing forbidden lines requires a basic flexibility of identity and an engagement with the serious play that is the creative use of the male body.

Simple stuff, but also heroic. Heroic not because dangerous — though certainly that — but because with each transit across a boundary, some sense of the stability of selfhood is released and given up. And as one gives up the stable identity, the Self, one is repeatedly grazed by “anonymity”. And anonymity is where the animal lives.

In the journal that he wrote in the last years of his life, after retiring from New York City to New England, he recounted his sexual experiences from the age of three to the age of 17. He rewrote the journal three times, each time telling the same stories and each time ending with his 18th birthday. It was as though he was trying to puzzle out how he’d become this phenomenon, how he’d developed to be Christopher Rage.

The last entries in the journal are especially telling. I’ll quote them in full.

9/5/89

“Death is on me like the fog is on this mountain. What a kick in the ass that is. On me. Wet. Insistent and clammy. Looking for a way into me like a nightmare bug that crawls in your ear or nose or mouth while you sleep. Maybe up your ass.

“And what a kick in the ass that is. Talk about your intimations of mortality. This is how death begins.

“It’s time to spit this out. This recollection. This memory. Nobody can do it for me. Like dying. Like living.

“I’ll write it like I lived it with no planning and little afterthought. Throw it up, write it down, turn it in.

“And mistakes? There are no mistakes. There are no accidents. Which is like saying it’s all accidents. (Swim little sperm.) Which is not like saying it’s all mistakes.”

“Don’t you get sweaty. This isn’t about death. It’s about sex. It begins with sex and while it might take the money of a Rockefeller to ensure that it ends with sex, there is something orgasmic about life leaving the body. There ought to be. That’s how it begins. I like the symmetry. I’m pretty sure there will be. And I usually get what I want. I always get what I need.

“Beginning with the earliest memories that form my conscious self, I always liked two things: Being alone and having sex. Alone is a state of mind for me, a closed door between me and the party. I want the door locked from my side. I want to hear the party. I want to be able to wander through it. And then I want to close the door and lock it. Simple enough.”

2/90 [final entry]

“Now that it’s ending, I want to hear my mother say don’t let the screen door slam, and then I want to hear it slam. It never did make that much noise, but I want to hear it anyway. And the front door, the aluminum one with our initial on it. I want to hear that one slam too. And Mom. And my father sing like the night he taught me the harmony to ‘Side by Side’.

“My parents never called me Chris.”

This last sentence wasn’t typed, as the rest of the journal had been. It’s the only sentence that’s scrawled by hand, in pen. Every man who’s built a life in pornography knows the peculiar and definite solitude that comes from living through a second identity. To a certain extent, it’s the whole point. Rage’s parents never knew about his career in porn. He never allowed any of his tapes to be sold in the state in which they lived. They knew nothing of the work and the life for which the man who had been their son was now infamous. This last journal entry is a poignant measure of the necessary and isolating distance a life in the business can demand.

The journal is signed “TCR 41”. Trey Christopher Rage, 41 years old.

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

So, “Christopher Rage”. Not his real name; yet certainly his real name. He chose it early in his career. Coined in 1980 as a hubristic joke — “All the rage on Christopher Street” — it came to denote a far more entrenched and defiant stance against a world that was smiling with indifference as everyone and everything died.

The titles all begin with it: “Christopher Rage’s OUTRAGE”; “Christopher Rage’s TRAMPS”; “Christopher Rage’s FUCKED UP”; “Christopher Rage’s MY MASTERS” and so on. He understood that the freedom of true anonymity, such as he longed for and needed throughout his life, is reserved for the famous. And so he constructed his own fame and the fame in turn constructed him.

“Christopher Rage” became an icon of sorts, a model of strength in transgression for those who knew and followed his work. And the small but intense fame that was his enabled the man who had begun as Frederick Mongue III, a Catholic boy born in Oklahoma, the son of a postal clerk, to hunt with defiance the animal in every man.

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Read More of Paul’s Papers HERE

was the journal you describe published or able to be found in any way?